McLaren M23 Formula One Racecar (Serial# M23/1)

Owner: Phil Mauger

City: Christchurch, New Zealand

Model: 1973 McLaren M23

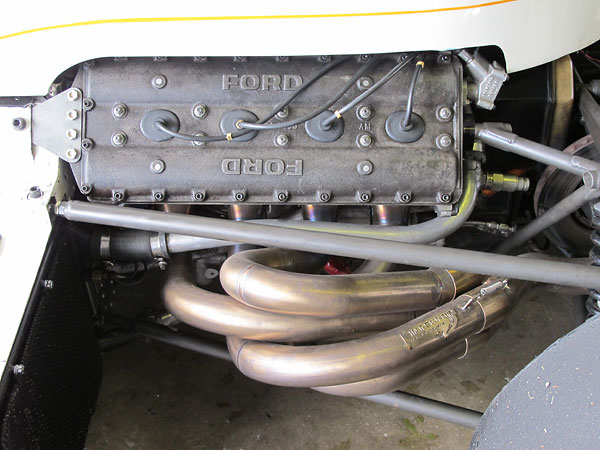

Engine: Ford Cosworth DFV V8 (3L)

Prepared by: John Crawford

Denny Hulme's McLaren M23 Returns to Watkins Glen

McLaren's M23 model is among the most enduringly successful designs in Grand Prix racing history. The M23 was competitive at the top tier of Formula One racing over a remarkable five season career, spanning 1973 through 1977. The M23 delivered Formula One's Constructors Championship to McLaren in 1974. Emerson Fittipaldi and James Hunt drove M23s to Formula One Drivers Championships in 1974 and 1976 respectively.

The very first M23 was completed late and pressed into service after just a couple days of testing. It had already missed the first two races of the 1973 season, but it would be driven by Denny Hulme for the whole balance of the year. That car, "M23/1", was quick right out of the box, achieving pole position at its first two races! At two other races, Hulme posted the quickest laps of any entrant. One of these was the inaugural Swedish Grand Prix, which Hulme won with an exceptionally strong finish. Hulme had been delayed at mid-race when flying sand jammed-up one of his throttle slides, but on his way to the pits it worked itself clear. After losing twenty seconds on the leaders, "the bear" rampaged forward. He finally stole the lead from home-crowd favorite Ronnie Peterson on lap 79 of 80. Hulme's teammate, Peter Revson, drove another M23 to two wins of his own in 1973. All this was against exceptionally tough competition, including defending champion Jackie Stewart in his Tyrrell plus Emerson Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson in Lotus 72 racecars. The 1973 Formula One season came to its end at Watkins Glen, where Denny Hulme scored a fourth place finish in the United States Grand Prix.

Almost thirty-eight years later, in September 2011 McLaren M23/1 returned to Watkins Glen to race again. BritishRacecar.com was there with three cameras. Many others have written about the M23 model. We believe we're the first to document the McLaren M23's design and construction with over sixty large, close-up, color photos.

About the McLaren M23's Place in History

The McLaren M23 was immediately preceded by a more curvaceous model known as the "M19". The M19 had been designed by Australian engineer Ralph Bellamy, who left McLaren and returned to his previous employer: Brabham. Frankly, it hadn't been a particularly successful design. It hadn't scored any race victories in its first year, and with it the McLaren team had only placed sixth in the 1971 Constructors Championship. 1972 was only a little better: one championship series race victory and third in Constructors points. Like many of its contemporaries the M19 was made obsolete by new Formula One safety regulations. It didn't have sufficient "deformable structure" protecting its fuel cells.

Responsibility for McLaren's new M23 model was assigned to Gordon Coppuck who had previously designed McLaren's Can-Am and Indy cars. Coppuck had most recently designed the 1972 Indianapolis 500 winning McLaren M16. As one would expect, the pragmatically wedge-shaped M16 foreshadowed the M23's design much more than the elaborately bulbous M19. Achieving a low polar moment of inertia had been a design priority; it made the car more nimble. To this end the M16 had featured hip-mounted radiators. On the other hand, an inboard mounted fuel cell spaced apart the driver and engine. One feature of the M19 was carried over intact. The M19's rising-rate front suspension, once developed, had begun to work well. It facilitated a lower front ride height, which was a big aerodynamic advantage. Other than front suspension, the M23 design was pretty much completely new.

As mentioned already, new Formula One rules called for deformable structure to protect fuel cells from side impacts. Coppuck's interpretation of this rule led him to develop non-detachable side pods which channeled air into the dual side-mounted radiators. Interestingly, rather than place the radiators inside the side pods he instead bolted them onto the back. The side pods are an early example of "composite sandwich" construction: between an outer wall of aluminum and an inner wall of fiberglass, Coppuck specified a measured charge of aerosol spray foam and hardening catalyst. Inboard of the side pods, the spaces between inner and outer aluminum monocoque skins were similarly stiffened with two-pack foam.

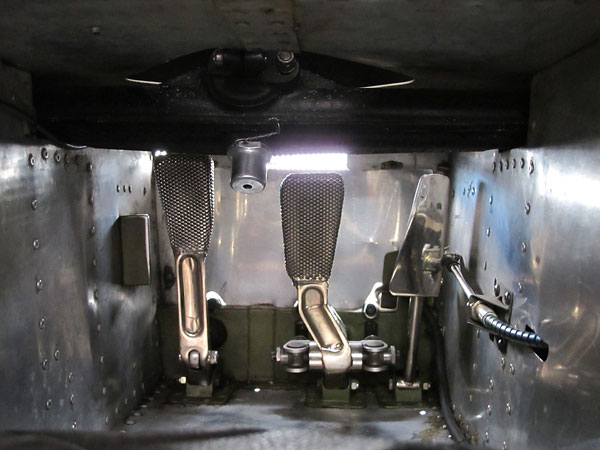

Modern racers take for granted quick-release steering wheel hubs. The McLaren M23 was one of the first racecars to come standard with this important feature. It was especially needed because the M23 has a very narrow cockpit and because since 1971 Formula One rules had mandated that drivers must be able to be evacuated from the cockpit in less than five seconds.

The McLaren works was located directly across a cul-de-sac from the Graviner fire extinguisher company. Graviner helped McLaren stay on top of fire safety developments, and McLaren helped Graviner become the preferred supplier throughout Formula One racing. McLaren M23/1 is credited as the first Formula One car equipped with a medical air supply plumbed to the driver's helmet and configured to automatically turn on in the event of an accident. It ran with a Graviner life support system at Zolder on May 20, 1973. Graviner had access to and knowledge of the necessary components because they had long been used in high altitude aviation. Similar systems were mandated by Formula One rules starting in 1979.

McLaren's M23 model is credited with twenty championship-qualifying Grand Prix victories. Development problems with its replacement, the McLaren M26, resulted in an extended phase-out for the M23. The McLaren works team entered M23s in eleven of 1977's seventeen races. Second tier teams entered McLaren M23s in fourteen of sixteen races of the 1978 season. Very few racecars have proved as adaptable to the changing technical requirements of their era.

McLaren M23/1 had a two year racing career. In 1973 it was driven by 1967 Grand Prix World Champion

driver Denny Hulme. In 1974 the McLaren team provided Hulme a brand new racecar and M23/1 was

updated to M23B specification for driver Mike Hailwood. M23/1 displayed similar Yardley soap and

cosmetics company livery in both 1973 and 1974, but its racing number was updated from "7" to "33".

1973 Season - Denny Hulme (NZ) in McLaren M23/1

Date Race Name Venue Results Comments

3/3 South African GP Kyalami Q1 F5 Hulme leading until a punctured tire forced pit stop.

3/17 Race of Champions Brands Hatch Q1 F2 Hulme leading w/ 5 laps to go when clutch failed.

4/8 BRDC Intl. Trophy Silverstone Q5 DNF (engine failure)

4/29 Spanish GP Barcelona Q2 F6

5/20 Belgian GP Zolder Q2 F7

6/3 Monaco GP Monte Carlo Q3 F6

6/17 Swedish GP Anderstorp Q6 F1 Hulme posted fastest lap of race, at 104.04mph.

7/1 French GP Paul Ricard Q6 F8 Hulme posted fastest lap of race, at 117.51mph.

7/14 British GP Silverstone Q2 F3 Teammate Revson: Q3 F1. (Scheckter: shunt!)

7/29 Dutch GP Zandvort Q4 DNF (engine failure)

8/5 German GP Nürburgring Q8 F12

8/19 Austrian GP Österreichring Q3 F8

9/9 Italian GP Monza Q3 F15 Teammate Peter Revson qualified 2nd, finished 3rd.

9/23 Canadian GP Mosport Q7 F13 Teammate Peter Revson qualified 2nd, finished 1st.

10/7 United States GP Watkins Glen Q8 F4

World Drivers Championship: 6th Place

1974 Season - Mike Hailwood (GB) in McLaren M23/1

Date Race Name Venue Results Comments

1-13 Argentine GP Buenos Aires Q9 F4 Teammate Hulme won. Teammate Fittipaldi debuted.

1-27 Brazilian GP Interlagos Q7 F5 Teammate Fittipaldi qualified fastest & won race.

3-17 Race of Champions Brands Hatch Q7 F4

3-30 South African GP Kyalami Q12 F3

5-26 Monaco GP Monte Carlo Q10 DNF (shunt)

7-7 French GP Dijon Q6 F7

7-20 British GP Brands Hatch Q11 DNF (spun) Fittipaldi qualified 8th & finished 2nd.

8-4 German GP Nürburgring N/A (shunt in pre-race practice)

World Drivers Championship: 10th Place (tied)

note: Mike Hailwood crashed M23/1 heavily in practice for the German Grand Prix, ending the car's Grand Prix career. Hailwood then qualified and raced spare chassis "M23B/7". In this second car, Hailwood crashed again and suffered a serious leg injury. The McLaren team rebuilt M23/1 to a suitable standard for demonstration use and presented it to Denny Hulme. The remains of M23B/7 were scrapped.

1973 Season - Denny Hulme (NZ) in McLaren M23/1

Date Race Name Venue Results Comments

03-mar South African GP Kyalami Q1 F5 Hulme leading until a punctured tire forced pit stop.

mar-17 Race of Champions Brands Hatch Q1 F2 Hulme leading w/ 5 laps to go when clutch failed.

04-ago BRDC Intl. Trophy Silverstone Q5 DNF (engine failure)

abr-29 Spanish GP Barcelona Q2 F6

may-20 Belgian GP Zolder Q2 F7

06-mar Monaco GP Monte Carlo Q3 F6

jun-17 Swedish GP Anderstorp Q6 F1 Hulme posted fastest lap of race, at 104.04mph.

07-ene French GP Paul Ricard Q6 F8 Hulme posted fastest lap of race, at 117.51mph.

jul-14 British GP Silverstone Q2 F3 Teammate Revson: Q3 F1. (Scheckter: shunt!)

jul-29 Dutch GP Zandvort Q4 DNF (engine failure)

08-may German GP Nürburgring Q8 F12

ago-19 Austrian GP Österreichring Q3 F8

09-sep Italian GP Monza Q3 F15 Teammate Peter Revson qualified 2nd, finished 3rd.

sep-23 Canadian GP Mosport Q7 F13 Teammate Peter Revson qualified 2nd, finished 1st.

10-jul United States GP Watkins Glen Q8 F4

World Drivers Championship: 6th Place

1974 Season - Mike Hailwood (GB) in McLaren M23/1

Date Race Name Venue Results Comments

ene-13 Argentine GP Buenos Aires Q9 F4 Teammate Hulme won. Teammate Fittipaldi debuted.

ene-27 Brazilian GP Interlagos Q7 F5 Teammate Fittipaldi qualified fastest & won race.

mar-17 Race of Champions Brands Hatch Q7 F4

mar-30 South African GP Kyalami Q12 F3

may-26 Monaco GP Monte Carlo Q10 DNF (shunt)

07-jul French GP Dijon Q6 F7

jul-20 British GP Brands Hatch Q11 DNF (spun) Fittipaldi qualified 8th & finished 2nd.

08-abr German GP Nürburgring N/A (shunt in pre-race practice)

World Drivers Championship: 10th Place (tied)

note: Mike Hailwood crashed M23/1 heavily in practice for the German Grand Prix, ending the car's Grand Prix career. Hailwood then qualified and raced spare chassis "M23B/7". In this second car, Hailwood crashed again and suffered a serious leg injury. The McLaren team rebuilt M23/1 to a suitable standard for demonstration use and presented it to Denny Hulme. The remains of M23B/7 were scrapped.*

McLaren M23 Production History

How many McLaren M23s were built? The serial number sequence starts at one and runs through fourteen, skipping number "13" for luck. (There are two other anomalies in the sequence. When faced with a need to rush a newly-built tenth car through Swiss customs, it proved expeditious to stamp number "8" onto its chassis plate. This small deception was rectified by amending the number 8 with a "dash 2". The original eighth M23 had been wrecked, but it was later repaired and issued chassis plate number "10".)

There are five basic M23 design iterations, which correspond generally to five years of construction. Distinctions between the five specifications are blurry for various reasons, not the least of which is that cars were updated throughout their respective careers. Cars were in fact modified for the unique requirements of almost every race entered. Formula One's habit of implementing rules changes mid-season also complicates issues.

Four M23s were built in 1973, followed by four more in 1974. The 1974 cars feature a longer wheelbase to suit a rule change pertaining to reducing rear wing overhang distance. Other changes for 1974 included modifications to the front suspension, parallel links in lieu of inverted A-arms for the rear suspension's lower connections, and wider rear track.

In 1975, McLaren built two more M23s, which featured revised front and rear suspensions. Other changes for 1975 included a different airbox, addition of a driver adjustable front anti-roll bar, a shorter nose, and altered side pods.

No new cars were built for 1976, but some of the existing cars were updated to a revised specification which included a new low-profile airbox to suit the latest rule change. Other changes for 1976 included addition of a driver adjustable rear anti-roll bar, substitution of an air starter for the previous electric starter, substitution of a six speed gearbox for the previous five speed gearbox, and installation of a different cockpit surround (which utilized Kevlar instead of glass fiber for a substantial weight reduction!)

In 1977, McLaren built three final M23 racecars to a fifth level of specification, which included redesigned front uprights to suit new Goodyear tires.

McLaren briefly flirted with offering a modified version of the M23 for Formula 5000. The essential difference would be with use of production-based 5.0L Chevrolet V8 engines in lieu of race-bred 3.0L Cosworth DFV V8 engines. Exactly one car of this type was built. For various reasons, the debut of McLaren M25/1 was considerably delayed. It only participated in two Formula 5000 races near the end of the 1976 season. M25/1 showed remarkable potential: Bob Evans drove it to a second place finish at Brands Hatch! Then, his engine suffered a broken piston midway through next race of the series. Formula 5000 ceased to exist in England after just three more races, but in an interesting turn of events M25/1 was rebuilt with a Cosworth DFV and was raced in nine "British Formula One" series races during 1977 and 1978. M25/1 has since been rebuilt to F5000 specifications for vintage racing.

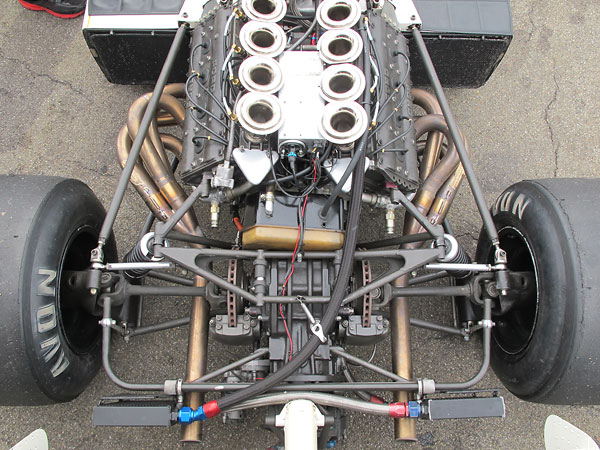

Features and Specifications

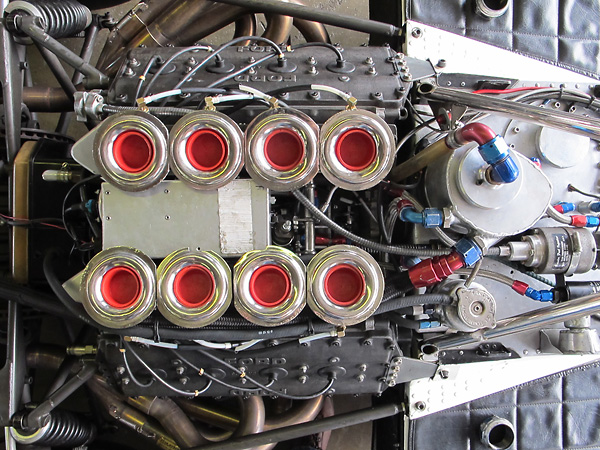

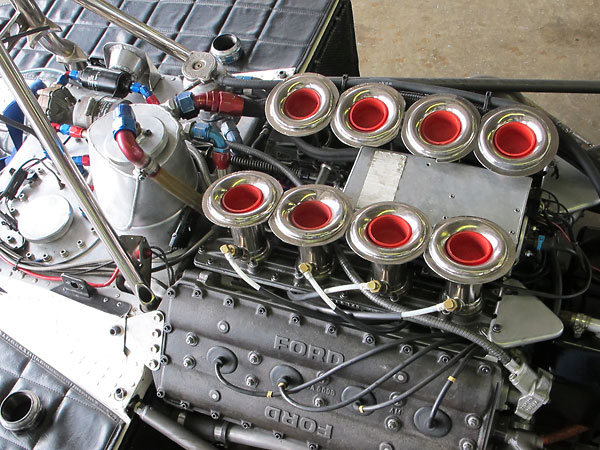

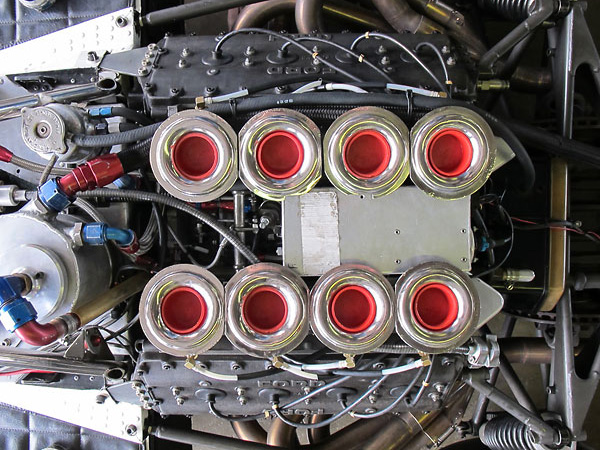

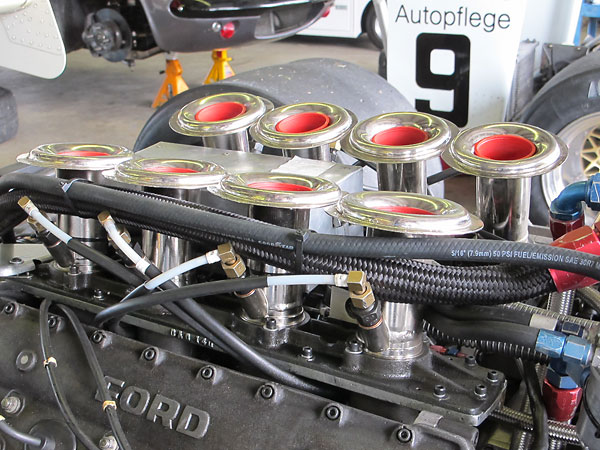

Engine: Ford Cosworth DFV V8 engine number 138, as delivered new to McLaren Racing in April 1973, rebuilt by Steve Weeber's Performance Engine Centre Ltd. in Christchurch, New Zealand. (2993cc. 3.373" bore x 2.555" stroke. 11.0:1 static compression ratio. Rated 465bhp @ 10,500rpm.) New cylinder heads sourced from the Cosworth plant in Torrance California. Lucas mechanical fuel injection. Lucas OPUS (Oscillating Pick-Up System) electronic ignition system. Bosch ignition coil. Champion G56R spark plugs. Dry sump lubrication system.

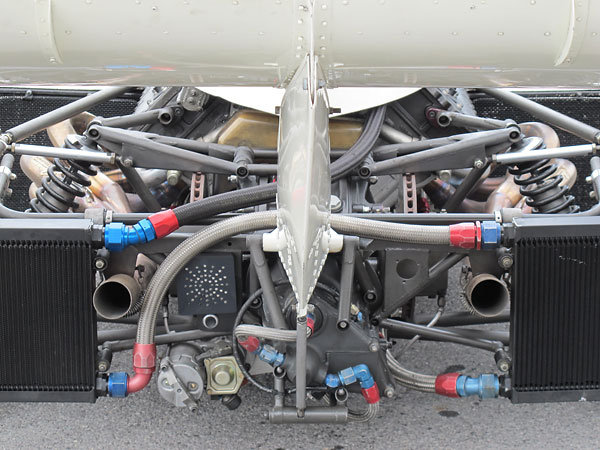

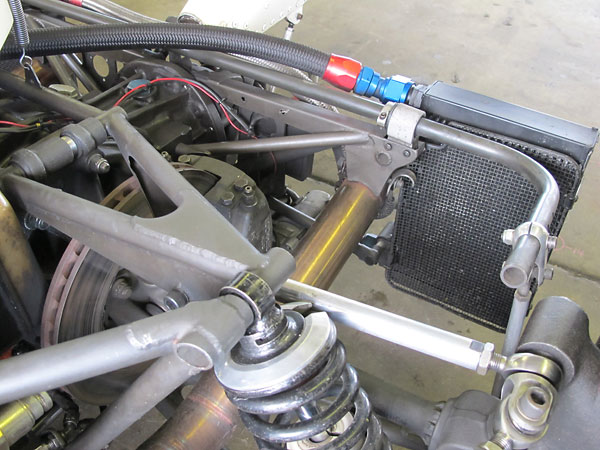

Cooling: dual radiators. Dual 25-row oil coolers.

Exhaust: Simpson Race Exhausts custom fabricated stainless steel four-into-one headers.

Transaxle: Hewland FG400 five speed, rebuilt by BPA Engineering Ltd. Girling master cylinder.

Chassis: 101" wheelbase, 65" front track, 62.5" rear track.

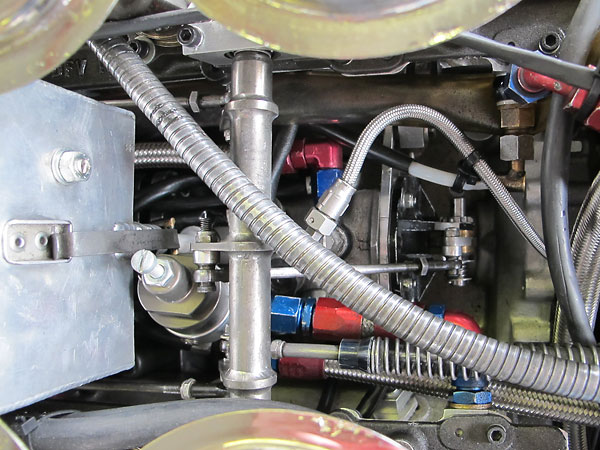

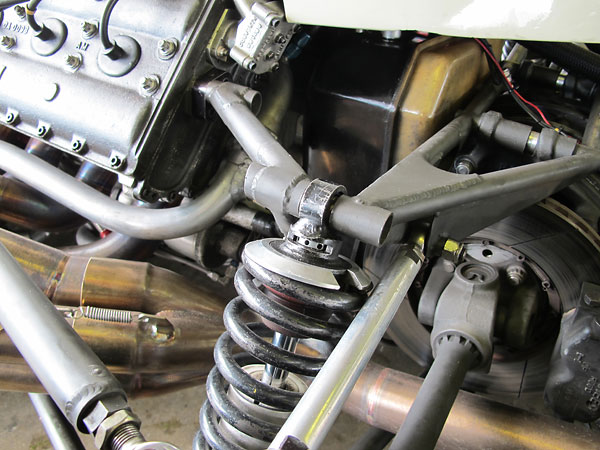

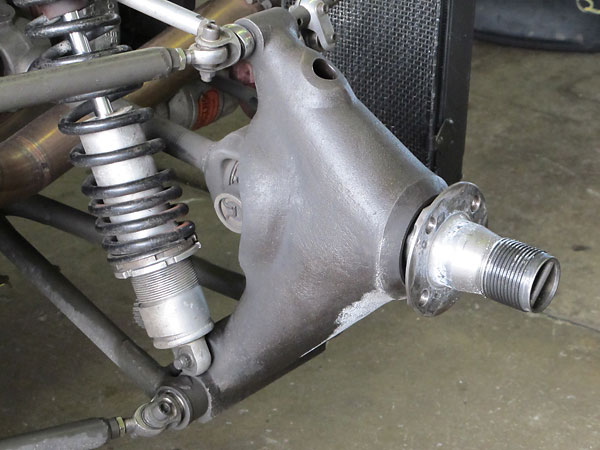

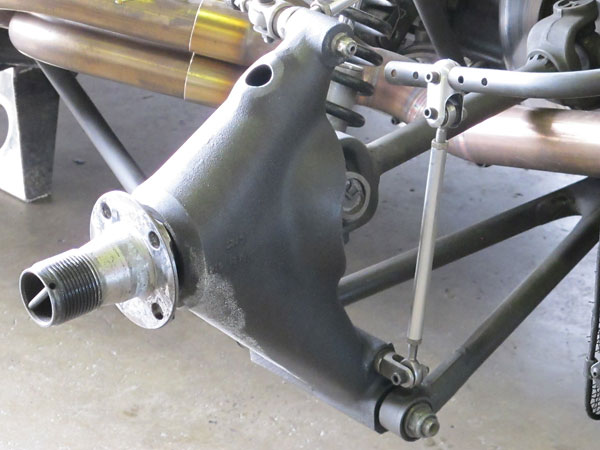

Front Susp.: wide based lower wishbones with twin-plane triangulated upper control arms. McLaren proprietary magnesium uprights. Pull-rod actuated rockers. Vertical, inboard mounted aluminum-bodied double adjustable KONI model 8212 coilover shock absorbers. Proprietary magnesium uprights with live stub axles. Anti-roll bar, operated by inboard-mounted linkage.

Rear Susp.: reversed lower wishbones, adjustable top links, and dual trailing links. McLaren proprietary magnesium uprights. Aluminum-bodied double adjustable KONI model 8212 coilover shock absorbers. Custom coil springs designed to become progressively coil-bound under load. Tubular adjustable (5-position) anti-sway bar.

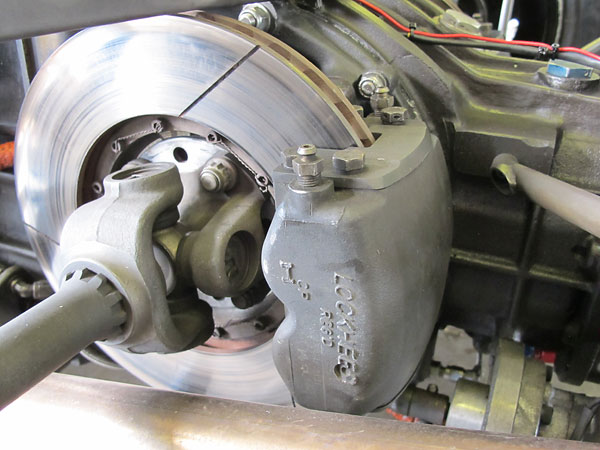

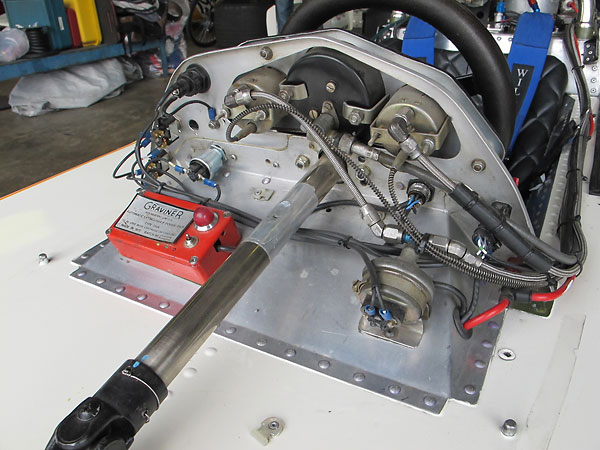

Brakes: (master) dual Girling master cylinders with integral reservoirs. Bias bar.

(front) Lockheed four piston calipers with 10.5" vented rotors (outboard-mounted),

(rear) Lockheed four piston calipers with 10.5" vented rotors (inboard-mounted).

Wheels/Tires: McLaren magnesium racing wheels (13x11 front, 13x16-18 rear.) Avon racing tires (10.0/20.0/13 front and 15.0/26.0/13 rear.)

Electrical: Enersys Powersafe SBS sealed battery. Ark Racing starter motor.

Instruments: (left to right) Smiths dual fuel pressure (0-160psi) and water temperature (30-120C) gauge, Smiths Chronometric tachometer (0-12500rpm) with tattletale, and Smiths dual oil pressure (0-160psi) and oil temperature (30-120C) gauge.

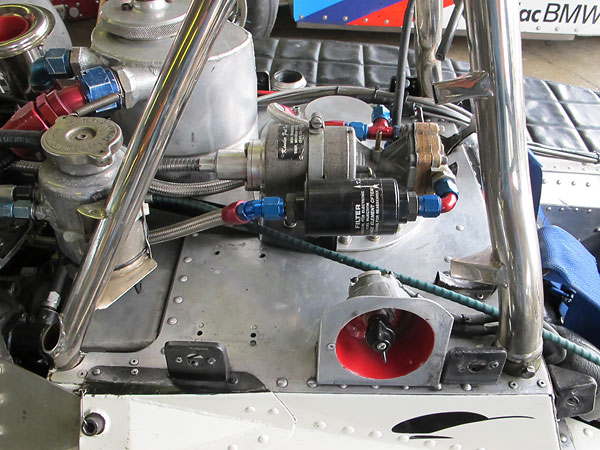

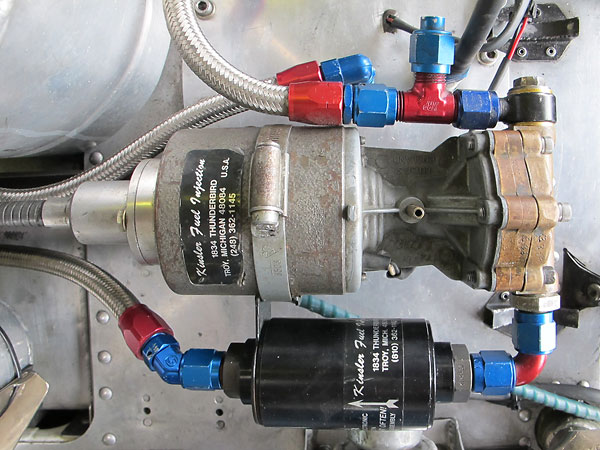

Fuel System: custom fuel cell (including rubber bladder and safety foam.) Kinsler cable-driven high pressure fuel pump. Kinsler fuel filter. Electric in-tank high pressure fuel pump.

Safety Eqmt: Willans six-point cam-lock safety harness. Quick release steering wheel hub. Graviner centralized fire suppression system.

Weight: ~1268# (34/66 front to rear).

Engine Installation

Fifteen of eighteen teams contesting the 1973 Grand Prix championship chose Cosworth's DFV

("Double Four Valve") V8 engines. In 1973 trim, these engines were probably producing about

460-465bhp. That's about 20-25bhp less than the Ferrari flat twelve, but more than BRM's V12.

The McLaren M23's fuel cell was located between the driver and the engine, instead of inside

pontoons on either side of the monocoque tub as had been McLaren's previous practice on F1

cars. The new location was reckoned safer and provided less variation in weight distribution as

fuel was consumed. Formula One fuel tank standards had changed rapidly, with rubber bladders

first mandated for the 1970 season and addition of safety foam mandated for the 1972 season.

At left: fuel cap. Mid-race refueling wasn't permitted in Formula One races during the M23's era.

At right: engine oil reservoir. Cosworth installation and operation instructions advised:

"Oil tanks should allow for approximate consumption of 6 pints during a G.P."

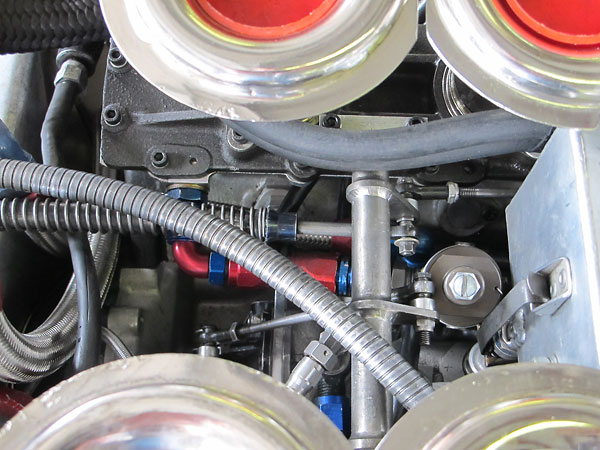

The intake stacks feature a full radius at the top to smooth entering airflow. Outboard of their radiused

section, they have a small flange where the airbox will seal to them. The engine draws its air supply

from a large plenum that's pressurized at racing speeds. More information about that appears below.

Lucas fuel injection, with one fuel injector per cylinder positioned upstream of a sliding throttle.

The function of Lucas' mechanical/timed nozzles is atomization only (i.e. not metering).

Earlier systems used "constant flow" nozzles, which actually metered fuel delivery as

a function of pressure drop across an orifice on the side of the nozzle.

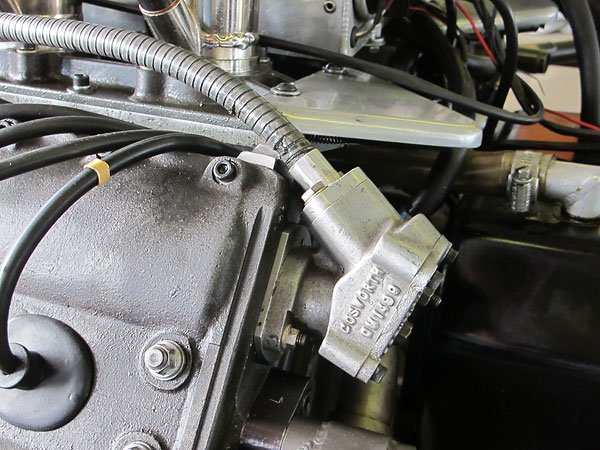

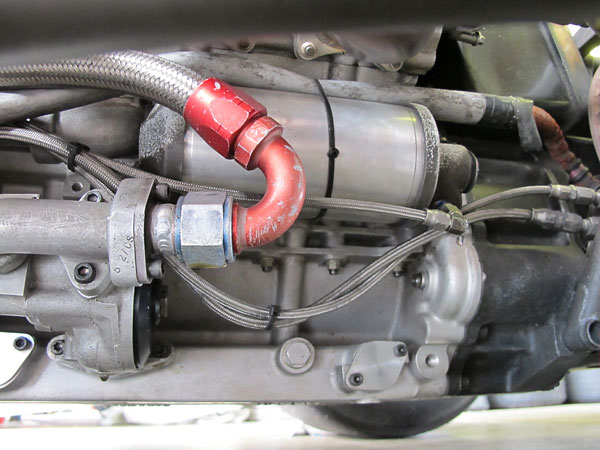

A high pressure mechanical fuel pump is driven via cable from one of the four camshafts.

Center: Kinsler high pressure mechanical fuel pump. A high pressure electric pump is

located in series with this one, but it's hidden inside the fuel cell. The electric pump is

only needed for starting the engine. After that, it's turned off.

Labels read: "Kinsler Fuel Injection, 1834 Thunderbird, Troy, Michigan 48084 U.S.A., (248) 362-1145"

At bottom: Kinsler fuel filter.

The Lucas Mk1 mechanical fuel injection metering unit is gear driven from off the crankshaft.

Throttle cable comes in from the left. A fuel pressure regulator can be seen at right.

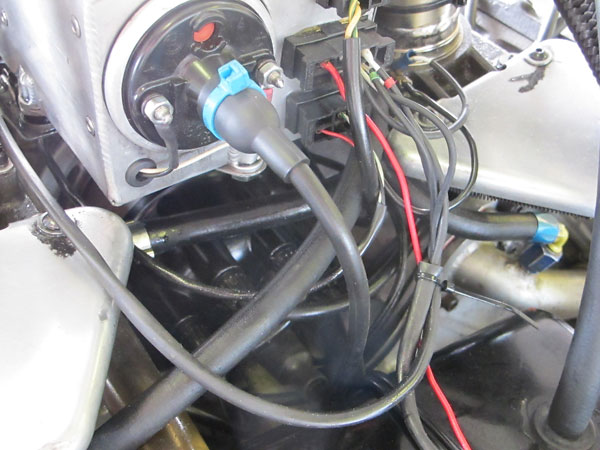

The DFV engine uses a Lucas OPUS ("Oscillating Pick-Up System") electronic ignition with a built-in

rev-limiter set at 10,500 rpm. Ignition timing is fixed at approximately 35° BTDC, triggered by

a variable reluctor sensor and a 40-tooth wheel on the front of the crankshaft. A conventional

distributor mounted in the engine's valley merely directs sparks to the respective cylinders.

The Smiths tachometer is cable-driven off the front end of one of the camshafts.

Interestingly, Cosworth literature warned: "The engine must not be allowed to idle

under 2000 rpm at any time or else excessive cam and tappet wear may result."

Pause to think about how many fasteners hold the magnesium valve covers to the

aluminum cylinder heads. No matter how you count, it's a lot of fasteners! Cosworth

promotional materials mentioned that their DFV engines were comprised of 3550

discrete parts, and that most of the parts required some amount of hand finishing.

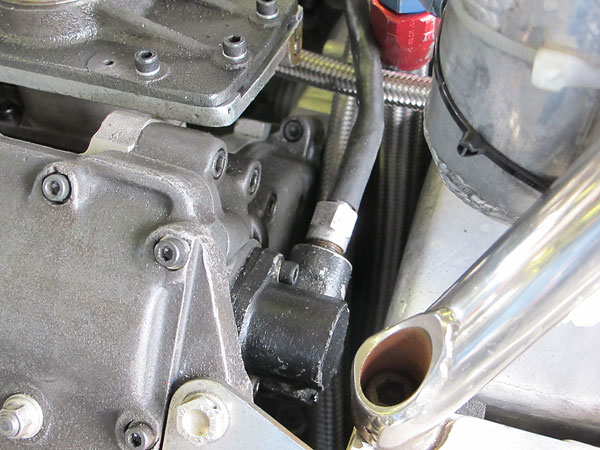

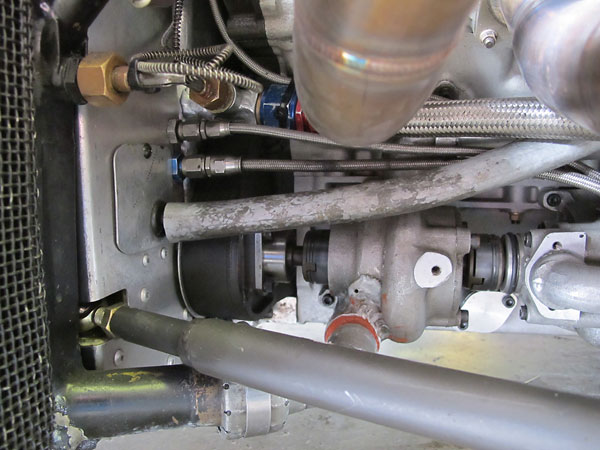

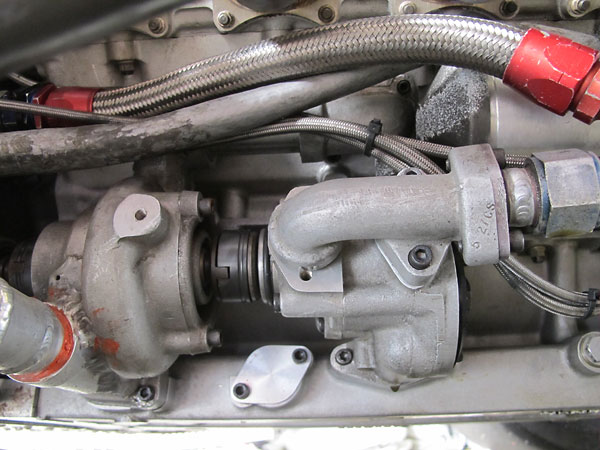

Two water pumps and two oil pumps... all belt-driven at one half of engine speed. This photo shows

one of two centrifugal water pumps. (The other water pump is on the opposite side of the engine.)

Behind and driven off of the left side water pump, the single-rotor high-pressure oil pump

should produce 80-90 psi at normal running speeds.

Canister oil filter (accepts Cosworth paper element oil filter part# PP0404).

Twin water pumps route water into the sides of the engine block. The water flows upwards to the

cylinder heads through three passages around each cylinder (two by the exhaust ports, one on the

intake side). Water exits the cylinder heads through flanges at the rear. Thermostats are mounted

externally. Water flows around the engine to the radiator through hard tubing.

Comment